“Don’t ask me where I’m from…” Do you recall the lyrics from “Olive Tree”, and the writer San Mao?

During the time when Taiwanese society was still very rigid, San Mao inspired many minds and souls who yearned for freedom with her wanderlust, foreign love stories, life in Sahara, and her prolific publication of over twenty literary works.

On 4 January 1991, San Mao ended her own life in Taipei. Her writings and cherished items were all donated to the National Museum of Taiwan Literature (NMTL). Thirty years after her passing, we come together with book-lovers of all generations to explore her free spirit and sincerity through her manuscripts and collections.

Her Life: A Name Synonymous With Nonconformity

San Mao was born Chen Mao-ping in 1943. She changed her name into Chen Ping later when she grew up, for she thought that character had too many strokes.

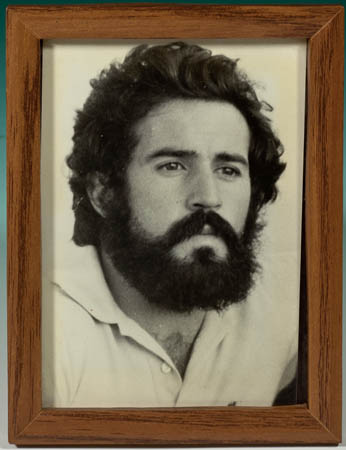

She didn’t like to study during junior high school but enjoyed reading. She then quit school and studied by herself from home. She liked writing and submitted works to Modern Literature magazine. She was then admitted to the Department of Philosophy at Chinese Culture University. In 1967, Chen Ping went to Spain alone and attended Madrid University. That was where she met José María Quero y Ruíz for the first time.

She returned to Taiwan to become a teacher in 1971 when her love life didn’t go well. Two years later, she returned to Spain and once again crossed path with Jose, who had then become a diver. It had been six years since they first met and they decided to go to Spanish Sahara together. They got married in 1974. In October of that year, she wrote about her life in Sahara under the title “Chinese Restaurant” and submitted it to the literary supplement of United Daily News under her penname San Mao.

Her Works: Taiwan’s Most Spectacular Travel Writing

The prose style of “Chinese Restaurant” was so uncommon to the readers in Taiwan and propelled the San Mao frenzy. She described how the desert people took a bath every four years and used water pipes to clean the inside of their bodies. Whether writing about unimaginable characters or romantic stories, San Mao wrote from a first-person point of view. They sounded like exaggeration or fictional, but her stories were real.

San Mao often wrote about the unique romance between herself and Jose. They once bought a car and nicknamed it "white horse", which was mentioned several times in her works. The license plate of the car, "SH-A3480" was also part of the donated collection, which inspired the NMTL to make a creative product-a sun-blocking umbrella. Following her 1976 essay collection titled “The Stories of the Sahara”, she then published “The Scarecrow’s Journal”, “The Crying Camel” and “The Tender Night”, which all became best-sellers. Even as of today, San Mao can be said to be the most influential and popular literati in Taiwan.

Her Era: The Spirit of Risk-taking for Freedom

In the sixth year of their marriage in 1979, Jose died in a diving accident. It was devastating and she quietly returned to Taipei and continued writing and traveling. In 1981, under the sponsorship of the United Daily News, she traveled to Central and South America and wrote “I Have Walked Thousands of Miles”. This marked the end of the San Mao Frenzy in Taiwan that lasted for 15 years.

The wanderings of San Mao in the desert and her foreign love stories opened new windows for the people of Taiwan to see the world beyond the confines of their homeland during those conservative times. San Mao occasionally was criticized for being a hypocrite or for not being truthful, but she firmly insisted that all her words are genuine. Authentic or imaginative, San Mao allowed people to understand that liberty and freedom is something that one must take a risk to fight for.

“My heart is filled with joy as I welcome this brand new year of 1991,” wrote San Mao in the opening of her final work, “It’s Also Nice to Dance a Song", which was completed at the end of 1990. She committed suicide at a hospital on 4 January 1991 and ender her legendary life at the age of 48.

More

San Mao is born in Chongqing, Sichuan Province on March 26th. Her father’s family came from Dinghai in Zhejiang Province. She is the second of four siblings with one older sister and two younger brothers. In an era of war and upheaval, San Mao was given the hope-filled birth name of Mao-ping (Peace Conferred), which combined the familial character Mao and the character Ping, meaning peace. The difficulties she had writing the intricate first character, however, encouraged San Mao to drop it from her name soon after starting school. Ping’s father subsequently followed her lead and struck the familial Mao from her brother’s names as well.

San Mao discovers her passion for reading early on as a student at Chung-Cheng Elementary School. She read voraciously and even snuck a copy of the risqué Chinese classic Dream of the Red Chambers during the fifth grade. Later on, she recalled experiencing a literary epiphany when she read the eloquent passage describing the parting of protagonist Bao Yu and his father. Literary aesthetics became her passion and her life’s work.

At Ku Fu-sheng’s introduction, San Mao publishes her first work Delusions (惑) in issue 15 of “Modern Literature” edited by Pai Hsien-yung. It marks the beginning of her literary career.

San Mao publishes her short story Moon River (月河) in the journal “Coronet” (Issue 6, Volume 19).

San Mao is invited by Chinese Cultural University founder Chang Chi-yun to attend CCU as a non-degree student in the philosophy department. Her academic performance while at CCU is exceptional.

San Mao leaves Taiwan to study in Madrid University’s School of Philosophy, where she meets Jose Maria Quero Y Ruiz. After completing her studies, she transfers to the Goethe Institute in Germany where she earns a German language teaching certificate in only nine months. She then travels to the United States where she finds work for a period in the University of Illinois’ Law Library.

San Mao accepts Chang Chi-yun’s invitation to teach in the German and Philosophy departments at the Chinese Cultural University.

San Mao’s German fiancé dies. Grief stricken, she leaves Taiwan once again. She reconnects with Jose in Spain.

San Mao and Jose decide to get married and in April the couple pack their bags and travel to the Sahara Desert.

San Mao and Jose register their marriage at a magistrate’s office in the Spanish Sahara (today’s Western Sahara).While life in the desert could be difficult, it was liberating for San Mo who began writing again. Her first piece, entitled China Hotel, was published in the United Daily New's supplement on October 6th. Praised personally by UDN's editor-in-chief Ping Hsin-tao, the submission marked the beginning of a rich stream of new literary output from San Mao.

San Mao completes her first literary compilation, Stories of the Sahara. The couple moves to Tenerife in the Canary Islands.

Jose dies in a diving accident. San Mao returns to Taiwan accompanied by her parents.

San Mao accepts an assistant professor position in creative arts in the Chinese Cultural University’s Chinese Language Department where she teaches courses on story and prose writing. Her classes are well received.

San Mao writes her first and only movie script, filmed and released under the title Red Dust. The movie, directed by Ho Yim and starring Chin Han, Brigitte Lin, and Maggie Cheung, went on to earn several Golden Horse film awards.

San Mao dies in the early morning of January 4th. She was 48 years old.

San Mao is born in Chongqing, Sichuan Province...

San Mao moves from China’s wartime capital of...

The entire family crosses over to Taiwan by fer...

San Mao discovers her passion for reading earl...

San Mao enters Taipei’s top girls’ high schoo...

At Ku Fu-sheng’s introduction, San Mao publish...

San Mao publishes her short story Moon River (月...

San Mao is invited by Chinese Cultural Univers...

San Mao leaves Taiwan to study in Madrid Univer...

San Mao accepts Chang Chi-yun’s invitation to...

San Mao’s German fiancé dies. Grief stricken,...

San Mao and Jose decide to get married and in A...

San Mao and Jose register their marriage at a ...

San Mao completes her first literary compilati...

Jose dies in a diving accident. San Mao returns...

San Mao decides to end her 14-year sojourn abr...

San Mao accepts an assistant professor positio...

San Mao stops teaching at the Chinese Cultural ...

San Mao makes her first return visit to China ...

San Mao writes her first and only movie script...

San Mao dies in the early morning of January 4t...

For her friends and families, it is not easy to describe Sanmao. Interestingly, she seems to assume quite different, even contrasting, appearances in their memories. Just like a desert rose. In the gusty and sandy desert wind from whence she was born and came, she was like a handful of soft grains; yet once out of the desert she became an enduring stone flower, peculiar and proud.

The most peculiar thing about Sanmao was her attitude toward money. She had seen harder days, and yet barely had a sense of number; neither would she work for money’s sake. In those difficult years, she just lived by plain rice mixed with soybean sauce; when she had some money, she spent it all on books and traveling. But could you say she was senseless? She was surely not. In every pocket of her clothes there would be some cash she’d forgotten, and when she found it she’d head straight for the bookstores.

She was not that senseless about number as her father said, for she was very exact when it came to honorariums. Yet she was tender-hearted: she might first be mad about how she only got two hundred NT dollars for one thousand words and rejected such offer; but then she would remember that the magazine was run by some idealistic young men who did not have much capital, so she changed her mind and showed her support. When other publishers were more courteous and gave her larger sums of honorariums, she just tucked them away without much care.

Everyone knows the famous Sanmao; yet the way we saw it, those credits did not seem to matter to her. She had always been Chen Ping, a soul that was honest to herself and always retained some childish innocence.

She said, in the desert there was almost no physiological need, but you still had a rich spiritual life…. She was attentive and serious when she said this, but her laughs, her hand gestures, even the movements she made when flicking her cigarettes, were so adorable and frank; all her experiences in life seemed to have brought her back to innocence.

It was her that made me envision the feel of freedom so vividly, made me realize what the world’s end meant for a writer…. Whenever I think of her, I still can’t regard her as simply a popular writer; instead, she showed us some measure of limited freedom with her own frail power; she showed to the mundane world that it was possible to live and die so fiercely.

Sanmao was ever so sensitive and tender. She always did what she could to help and support, to give what she had, to her friends, any friend. Even to the point of being dictatorial that she did not allow others to give back in return. How so unbelievable.

If you have ever read Sanmao, you’d know she was a good storyteller…when you talked with her, you noticed how innocent, and yet how mysterious she sometimes was, almost as she was a fictional character, and you couldn’t see clearly. Frankly, I only wish I could really keep her, and imagine her in my fantasy.

Sanmao was ever so sensitive to everything: people, nature, and things around her. Very few people have the same passion as she possessed—she was just like a candle burning brightly, and burnt out fast, before she could spread that light and warmth to too many people. At the end of Le Petit Prince, her favorite book, the Little Prince finds a way to return to his world…. Sanmao was that Little Prince (or Princess if you like). Maybe she was too fine to belong to this world. Now she has returned home, and I miss her. But I know: someday we will meet again.

I believe that the best way to commemorate Sanmao is to discard her legends and everything outside of her literature, and to read her writings from an objective and cool-headed point of view; to study her unique style and aesthetic quality; to examine her intensive artistic quality and inner energy—that is the most important way to understand and interpret Sanmao.

MoreBefore achieving fame pseudonymously as San Mao, Chen Ping wrote works of less refined technique on subjects that centered heavily on personal pains interspersed by flights of fancy. Despite the rawness of her early writings, they reflected sincerity and heterogeneous aesthetics as well as an affinity that already hints at the up-and-coming literary legend.

MoreSan Mao’s vivid and heart-rending Stories of the Sahara pique reader curiosity while prompting compassion and sympathy. Wrapped in sorrow and separated from beauty and romance, her tale conceals substantive inner truths. Hers is a crude realism that is capable of making flowers bloom from the arid desert.

MoreMore than a joining of two distinct cultures, San Mao’s relationship and marriage with Jose Ruiz was spiced with surprise, excitement and idiosyncrasy. Experiencing a path to love and romance significantly more tortured than the norm, San Mao used her corkscrew path to love and romance as fodder for an article she entitled, “Exotic Romance and Exceptional Fortune.” Readers today continue to be touched deeply by the indelible message of this piece.

Solemn purpose was never part of this author’s literary style. San Mao’s intimate familiarity with her own creative works made writing an intellectual game. Her words were impassioned and charming as well as fresh and absorbing. Her works engage readers with prose that rolls off the tongue.

MoreHer motley collection of trinkets and knick-knacks was San Mao's treasured time capsule. Memories of encounters in faraway lands infused each piece and provided a permanent record of her every precious, albeit fleeting, relationship. This collection helped keep alive for San Mao her life's highs and lows as well as her own unfolding saga. They were also talismans that helped fuel her ideas, actions, character and expression. Each piece was an integral part of the author's life and experiences. NMTL is pleased to present in this exhibit ten items from San Mao's collection of treasures accompanied by descriptions and stories.

Sanmao creative genre mainly in prose,fiction mainly,but also in translation,script writing;in terms of subject selection or artistic expression,there are a unique aesthetic and technique.Her rich experience of wandering,depicting colorful exotic scenery;with a keen feeling,to feelings of financial writing,showing the love of life,the spirit of nature,simple and unique romantic charm which touched the hearts of readers.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Sanmao Classics vol.8); October 2010AD,pages:295.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Sanmao Classics vol.7); October 2010AD,pages:253.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Sanmao Classics vol.6); December 2010AD,pages:303.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Sanmao Classics vol.5);October 2010AD,pages:287.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Sanmao Classics vol.4);November 2010AD,pages:239.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Sanmao Classics vol.3); December 2010AD,pages:295.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Sanmao Classics vol.2); January 2011AD,pages:363.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Sanmao Classics vol.1);January 2011AD,pages:367.

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company. August 2004AD.

Beijing: Contemporary World Press. October 2002AD,pages:844.

Hohhot: Inner Mongolia People’s Publishing House (Classic Literary Works and Writers Series)2002AD,pages:491;

Haikou: Nanhai Publishing House. October 2006AD.

Changchun: Jilin Photograph Publishing House (Classic Literary Works and Writers Series).2002AD,pages:468.

Shantou: Shantou University Press. May 2001AD,pages:394.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.3060) January 2001AD,pages:191;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.19). June 2003AD,pages:158.

Changchun: Time Literature and Art Press. March 2000AD,pages:544.

Changchun: Jilin Photograph Publishing House (Classic Literary Works and Writers). January 2000AD,pages:504.

Kuitun: Ili People’s Publishing House (Twentieth Century Classic Literary Texts for High School Mandarin Chinese Courses Series).2000AD,pages:334;

Changchun: Time Literature and Art Press (Twenty-First Century Literature for Young People). Edited by Yu Tao.2000AD,pages:284.

Kunming: Yunnan People’s Publishing House; June 1996AD,pages:504;

Taiyuan: Beiyue Literature and Art Publishing House (Modern Chinese Writers Classic Series) September 2001AD,pages:598.

Changchun: Jilin Photograph House (Twentieth Century Chinese Essay Classics)1999AD,pages:140.

Lanzhou: Dunhuang Literature and Art Press. December 1998AD,pages:392.

Chengdu: Chengdu Publishing House (Classic Literary Works and Writers). February 1996AD,pages:539.

Chengdu: Chengdu Publishing House (Classic Literary Works and Writers).May 1995AD,pages:526.

Yinchuan: Ningxia People’s Publishing House (Collected Works of Sanmao)1994AD,pages:139.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.2206); June 1993AD,pages:175;

Yinchuan: Ningxia People’s Publishing House (Collected Works of Sanmao); March 1994AD,pages:123;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.18); October 1996AD,pages:101;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.18). August 2003AD,pages:194.

Guilin: Lijiang Publishing Company (Taiwanese Women Writers Love-Words Series). March 2003AD,pages:211.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.2127); January 1993AD,pages:207;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.17); October 1996AD,pages:161;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.17).August 2003AD,pages:202.

Taiyuan: Hope Publishing House. August 1992AD,pages:207.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.1887);May 1991AD,pages:159;

Yinchuan: Ningxia People’s Publishing House (Collected Works of Sanmao);June 1994AD,pages:138;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.16); October 1996AD,pages:100;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.16),June 2003AD,pages:185.

Beijing: China International Radio Press (Hong Kong and Taiwan Literature Series)1991AD,pages:317.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.1507);July 1988AD,pages:342;

Xi’an: Shaanxi Travel Publishing Company;April 1989AD,pages:211;

Beijing: China Friendship Publishing Company;September 1989AD,pages:196;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao);July 1993,pages:207;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.14); October 1996AD,pages:252;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.14), August 1996AD,pages:252.

Fuzhou: Haixia Art and Literature Publishing House. September 1987AD,pages:179.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.1393); July 1987AD,pages:276;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao);July,1993AD,pages:221;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.13); October 1996AD,pages:270;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.13).April 2003AD,pages:321.

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press. February 1987AD,pages:466.

Beijing: China Women Publishing House. December 1986AD,pages:276.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.1106); March 1985AD,pages:125;

Beijing: China Friendship Publishing Company; June 1989AD,pages:99;

Xi’an: Shaanxi Travel Publishing Company;January 1993AD,pages:70;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao); July 1993AD,pages:159;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.12); October 1996AD,pages:161;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.12). August 2003AD,pages:164.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.1105); March 1985AD,pages:223;

Beijing: China Friendship Publishing Company; April 1989AD,pages:114;

Xi’an: Shaanxi Travel Publishing Company;January 1993AD,pages:106;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao); July 1993AD,pages:111;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.11); October 1996AD,pages:131;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.11).August 2003AD,pages:203.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.1104); March 1985AD,pages:301;

Beijing: China Friendship Publishing Company; 1987AD,pages:169;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao);July 1993AD,pages:184;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.10)October 1996AD,pages:228;

Hohhot: Inner Mongolia People’s Publishing House (Contemporary Chinese Essay Classics);March 2003AD,pages:464;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.10).August 2003AD,pages:204.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.990). March 1984AD,pages:177.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.900);July 1983AD,pages:252;

Xi’an: Shaanxi Travel Publishing Company;January 1993AD,pages:174;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao);July 1993AD,pages:152;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.9);

October 1996AD,pages:187.

Fujian: Fujian People’s Publishing House (Taiwanese Literature Series). May 1983AD,pages:312.

Taipei: Linking Books (United Daily Series); May 1982AD,pages:232;

Guilin: Lijiang Publishing Company; October 1986AD,pages:182;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao); July 1993AD,pages:177;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.8);

October 1996AD,pages:216;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.8). August 2003AD,pages:215.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.783)August 1981AD,pages:288;

Beijing: China Friendship Publishing Company August 1984AD,pages:193;

Xi’an: Shaanxi Travel Publishing Company January 1993AD,pages:188;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao) July 1993AD,pages:179;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.7)October 1996AD,pages:228.;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.7). August 2003AD,pages:275.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.782)August 1981AD,pages:285;

Beijing: China Friendship Publishing Company; November 1987AD,pages:195;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao)July 1993AD,pages:179;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.6)October 1996AD,pages:220;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.6). August 2003AD,pages:219

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.597)February 1979AD,pages:274;

Hong Kong: Nghingkee Bookstore 1982AD,pages:274;

Xi’an: Shaanxi Travel Publishing Company January 1993AD,pages:183; Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao) July 1993AD,pages:177;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.5) October 1996AD,pages:220;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.5)August 2003AD,pages:233;

Beijing: October Arts and Literature Publishing House (Collected Works of Sanmao).May 2007AD,pages:294

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.518)August 1977AD,pages:254;

Xi’an: Shaanxi Travel Publishing Company; January 1993AD,pages:168;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao)July 1993AD,pages:167;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.4) October 1996AD,pages:208;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.4)June 2003AD,pages:222.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.510)June 1977AD,pages:269;

Beijing: China Friendship Publishing Company; December 1985AD,pages:182;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House (Collected Essays of Sanmao)July 1993AD,pages:151;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.3) October 1996AD,pages:189;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.3). August 2003AD,pages:220.

Prose Taipei: Crown Publishing Company, July 1976AD,pages:250 (Crown Books series no.463);

Beijing: China Friendship Publishing Company; October 1985AD,pages:203;

Xi’an: Shaanxi Travel Publishing Company; January 1993AD,pages:185;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House; July 1993AD,pages:165;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press; October 1996AD,pages:189;

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company. August 2003AD,pages:189.

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company, May 1976 AD,pages:250 (Crown Books series no.454);

Beijing: China Friendship Publishing Company; September 1984 AD,pages:164;

Xi’an: Shaanxi Travel Publishing Company; January 1933AD,pages:173;

Changsha: Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House, July 1933AD,pages:166 (Collected Essays of Sanmao);

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press, October 1996AD,pages:207 (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.1);

Harbin: Harbin Publishing Company, August 2003AD,pages:216 (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.1);

Beijing: October Arts and Literature Publishing House , May 2007AD,pages:310(New Classics, Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.2).

Taipei: Crown Publishing Company (Crown Books series no.1834) December 1990AD,pages:205;

Beijing: The Writers Publishing House; March 1991AD,pages:267;

Yinchuan: Ningxia People’s Publishing House (Collected Works of Sanmao); March 1994AD,pages:158;

Guangzhou: Guangdong Travel and Tourism Press (Collected Works of Sanmao, vol.15); October 1996AD;

In her life, few things were more important to Sanmao than travel. In the two decades following the 1960s, when many were still unfamiliar with the idea of "travel."Sanmao had created her own cartographic stories, leaving footprints in Spain, Germany, Europe, the United States, African Sahara, Central and South America, China, etc. She had once said, “In my wandering travels, I never sought the idea of the romantic"; instead, she was seeking, in the déjà vu-like nostalgia, the ever-changing, ceaseless beauty of life.

Sanmao had wanted to visit Central and South America for a long time and was only deterred from lack of financial support. In 1981, under the sponsorship of Wang Tiwu from United Daily News, Sanmao finally departed on a six-month long trip in Central and South America, traveling with photographer Mi Xia.

MoreSanmao’s decision to go abroad was initially only a half-serious act in response to her boyfriend’s inaction. Out of mild exasperation, she ran through the necessary procedures, never expecting its realization in full sincerity. Yet that was how her destiny was sealed: she did go to Spain, Germany, and the United States…. Love drove her away, but had also changed the rest of her life.

MoreOut of penchant for wandering, in response to callings from afar, she left and went into the desert in search of the nostalgia from a previous life, determined to be the world’s first woman explorer to have crossed the Sahara Desert.

MoreSanmao had trice visited China: in 1989, she went back to Xiaosha Town to pay homage to her ancestors; in April 1990, she visited the west of China; in the summer of 1990, she headed toward the south of Yangzhi River and also went to the southwest part of China, but was inhibited from going to the Silk Road out of health concern.

More